Global Supply Chain Risk Exposed By COVID-19

In 2017, Hurricane Maria damaged the Puerto Rican power grid and caused worldwide shortages of IV saline fluids that lasted over a year. In 2019, Brexit and U.S. trade tariff negotiations raised questions about the stresses geopolitics can apply to fragile globally interdependent supply chains. Currently, the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) to the manufacturing sectors in China highlight the dangers of concentrating production in limited geographic regions.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria damaged the Puerto Rican power grid and caused worldwide shortages of IV saline fluids that lasted over a year. In 2019, Brexit and U.S. trade tariff negotiations raised questions about the stresses geopolitics can apply to fragile globally interdependent supply chains. Currently, the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) to the manufacturing sectors in China highlight the dangers of concentrating production in limited geographic regions.

We don’t need any more evidence. It is clear that man-made and natural disasters, political climates, and pandemic illnesses can all pose unique and life-threatening challenges to the world’s pharmaceutical global supply chains. Any one of these has the potential to destabilize supply chains and trigger shortages of drug product all over the world.

A reliable supply of medicinal product plays a critical role in protecting the world from threats when they need it most, such as infectious disease outbreaks and disaster situations. These products are produced by the private sector and monitored by the public sector, and as such collaboration and information sharing between the public and private sectors is essential to mounting effective response and recovery efforts across the world.

Whether we experience increased regional demand caused by disasters or increased global demand caused by a pandemic, one thing is clear – the conditions that cause demand to rise also threaten the stability of our global supply chains and our ability to meet the demand.

The Shift to Overseas Manufacturing

The United States’ investment into biomedical research made it the world’s leader in drug discovery and development. However, in order to direct that capital into discovery costs had to be cut elsewhere, most significantly in manufacturing. This resulted in the gradual movement of drug manufacturing to areas of the world that offer cheaper labor costs.

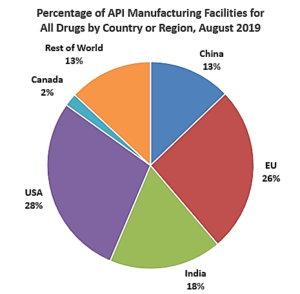

This shift impacted much of the supply chain, but most prominently with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Government data reports show that as of August 2019, only 28% of the manufacturing facilities making APIs to supply the U.S. market were located within U.S. borders. The remaining 72% were overseas, including 13 percent in China (which is more than double the number of registered Chinese API facilities in 2010).

The Risks to Integrity and Supply – We Can’t Mitigate Risk We Can’t Measure

This rapid expansion of the global market exposes our industry’s ability to supply the world’s demand to an exponential increase in risk. This includes some risks we have been talking about for years, including cyber risks, environmental risks, and security risks (intentional adulteration, cargo theft, counterfeiting, etc.). Each of those risks have been mitigated to some extent by efforts of the world’s regulating authorities to work together to harmonize regulations and share information and resources.

However, recent events have shown us that the risks we had been focusing on have been further exacerbated not only by limited visibility to the vulnerabilities inside other countries, but also the extent of (or lack of) redundancy in supply chains.

The FDA said it expects the outbreak of COVID-19 to cause “potential disruptions to supply or shortages of critical medical products in the U.S.”

Ron Piervincenzi, CEO of U.S. Pharmacopeia, added “Antibiotics are particularly at risk because about 85% of their ingredients come from China.”

For instance, while today’s law requires drug companies to notify the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) within five days of becoming aware of product shortages, it does not require the same of medical device companies.

Further, today’s licensing process does not require data that would give the FDA visibility to the number of drugs supplied to the U.S. that contain an ingredient sourced from a single country. Basically, the FDA does not collect data that would enable the agency to predict drugs that are vulnerable to shortages caused by regional or national disturbances. The disruption of the supply chain we are currently seeing also suggests that that individual companies are failing to use this type of data to manage their own supply chain risks.

The bottom line? The FDA doesn’t have the data it needs to measure or manage this risk. And if manufacturers do have it, it appears they aren’t using it.

Time to Adapt to a Proactive (Not Reactive) Supply Chain Risk Management Model

We know that none of the current options provided for under the law can be accomplished quickly. Registering and preparing a new facility or transferring operations from one registered facility to another or qualifying a new vendor and bringing in product from a new source are the options available to us. However, they all take time and money and could never be a viable resolution to a supply chain disruption in an emergency situation.

We know that none of the current options provided for under the law can be accomplished quickly. Registering and preparing a new facility or transferring operations from one registered facility to another or qualifying a new vendor and bringing in product from a new source are the options available to us. However, they all take time and money and could never be a viable resolution to a supply chain disruption in an emergency situation.

If you have been involved in an industry regulated by 21 CFR, you know that events that threaten health and human safety often highlight weaknesses in the model, prompting changes to the law. COVID-19 is just the latest in a string of events that have done just that, and it’s well past time for the consumer protection model to adapt again.

At this point, the FDA has not made future regulatory plans clear, but many people in industry have some very practical suggestions. Here are a few of mine:

Public Sector: Regulatory and Agency Changes

- Adapt the licensing model to require the definition of redundancy levels in supply chains so that risk can be profiled by drug (single manufacturer) and drug type (across all manufacturers).

- Expand government stockpiling of drugs at risk, prioritized on criticality of the product to the populous, as is already the case for vaccines.

- Implement a tech transfer approval process that can fast-track operational location changes in emergency situations for lifesaving or critical products.

- Implement an emergency protocol for regional situations that prompt evacuation of American personnel from foreign countries (e.g., who inspects Chinese manufacturing plants if all U.S. citizens were evacuated from China? Do we increase inspection of imports if our ability to inspect overseas plants decreases?).

- Expand the scope to the requirement for product shortages notifications to include medical device and API manufacturers.

- Require manufacturers to declare the reason for a projected shortage, the expected duration, and shortage mitigation plans (including timelines for resolution).

- Implement surveillance programs that are capable of determining whether or not these new tools are effective.

- Appoint a spokesperson to focus on communicating these plans and their effectiveness to the public, which could mitigate panic on Main Street and Wall Street.

Private Sector: Corporate and Operational Changes

- Develop supply chain emergency response plans that can be implemented to quickly adapt acquisition and tech transfer processes in response to emergency situations.

- Adapt supplier quality procedures to include measuring vulnerabilities of regions, and to include elevating the risk associated to suppliers in those regions.

- Adapt product-based risk management processes to include risk contributed by the reliability of the supply chain.

- Use the data to measure and increase redundancy in supply chains.

In light of these vulnerabilities made clear by all of the examples cited — most recently by COVID-19 — it is imperative that we develop an aggressive plan for not only collaboratively and effectively responding to supply chain disruptions, but for reducing the probability of their occurrence.

This type of collaborative proactive risk management has been largely absent in both our public and private sector models. This is something we can and should change.

© Coda Corp USA 2020. All rights reserved.

__________________________

Author:

Gina Guido-Redden

COO, Coda Corp USA

This article can also be seen in The RQA publication, Quasar:

Gina Guido-Redden, “How Coronavirus, Brexit and Hurricanes Are Impacting the Global Supply Chain,” Quasar #152 (July 2020) ISSN 1463-1768: 28-31.

Gina Guido-Redden is a quality and regulatory professional with over 25 years of domestic and international industry experience. She is the co-founder and chief operations officer of Coda Corp USA, which provides consultancy services to pharmaceutical, biologics and medical device firms.

Gina Guido-Redden is a quality and regulatory professional with over 25 years of domestic and international industry experience. She is the co-founder and chief operations officer of Coda Corp USA, which provides consultancy services to pharmaceutical, biologics and medical device firms.

Guido-Redden’s history specializes in the areas of facility start up, regulatory compliance and remediation, quality system development, mentorship and training, quality system design, and implementation and management.

She is also a quality systems subject matter expert (SME), frequent seminar presenter, and content contributor to industry publications, including GAMP’s White Paper on Part 11, The Journal of Validation Technology, New Generation Pharmaceuticals, Computer Validation Digest, and MasterControl’s GxP Lifeline. Coda Corp USA is an enterprise partner of MasterControl.

NAVIGATION

NAVIGATION